If you are close to my age, you surely remember Pearl Jam. You remember them, along with their darker siblings Nirvana, owning MTV and rock radio during the first half of the 1990's. You remember them appearing in a dense array of Video Music Awards and Lollapaloozas and SNL performances, first as astonishingly exuberant, fresh-faced, hair-enveloped kids and then as gloomy, somewhat less hairy iconoclasts. You remember the flannels and the Doc Martens and the skate shorts worn over colorful long underwear.

You probably remember that Pearl Jam and Nirvana were the avatars of a thing called "grunge," soon subsumed under the aegis of "Alternative Rock," terms that both became hopelessly dated lazy-dad-rock-critic fodder basically before they had even been uttered. Both terms did, however, signify a sudden emergence of a previously underground sound and ethos into the mainstream. These bands were the more approachable, user-friendly heirs of '80's noisemakers like Sonic Youth, The Pixies, The Melvins, and Fugazi (among many, many others). And to kids like me who had been fed a steady diet of Def Leppard and New Edition, there certainly seemed to be something radical and mysterious about Pearl Jam's music.

Nevertheless, despite their position as torchbearers of grunge (ugh, its really hard to even write that term) and despite the fact that their founding members were veterans of Seattle's underground scene, Pearl Jam were always slightly out of place in the cultural moment they inhabited.

Ten, their debut record, was glossier and more arena-ready than the music of any of their cohorts. Their touchstones were as much The Who, Cheap Trick and the Cult as the Germs and Minor Threat. They had more than enough charisma and bombast to play stadiums, but they were too grave and hook-less for the hair bands. They weren't heavy enough to be heavy. They were too glammy to be punk, too earnest for the indie rockers. It was classic rock without the bluesy swagger, glam without the irony, punk without the musical purity.

And then there was that infamous bellow. If you remember anything about Pearl Jam, you remember the bellow. Easily mocked, relentlessly copied (indeed: the bellow was much more easily mocked thanks to the unintentional burlesque-ing given it by its many imitators ),

Eddie Vedder's deep, horse roar quickly became a signifier for an operatic melancholy that frequently spilled over into affected self-seriousness. (If you've never heard the bellow or have somehow forgotten what it sounds like, imagine this in your mind's throatiest baritone:

heeeeevaan, shamalama dabadaba hamalama, etc,

hhyeeeeah, and so on.) It was Vedder's signature, the voice in which he declaimed his dramas of grade school suicides and incest-victims-turned-serial-killers. It is a voice that, unfortunately for all of us, still resonates through the chords of the plangent, emotionally overbearing confessional-mode that has permeated rock radio every since.

And so, despite (and of course because of) their breathtaking success--a success founded on that very emotionalism and bombast and rock-historical conservatism--Pearl Jam were really uncool. Which was ok with me because in the early '90's (and, well, throughout the middle and most of the late '90's) I was pretty uncool myself. I was a smart enough kid, exceptionally sensitive (in both senses of the word: acutely aware of the world and also easily wounded), but not all that culturally well-informed. Call it the eldest child effect. I didn't have a cool older sister forcing me to read

Slaughterhouse-Five or recommending that instead of sitting alone in my room listening to baseball games on the radio or doing pushups while blasting Jimi Hendrix I should maybe accompany her to that Pavement show at 1st Avenue. I didn't know any better.

In other words, Pearl Jam was made for me. I wasn't sophisticated enough to be snobbish about their lack of avant-rock cred, as I certainly would have been had they emerged ten years later. And, as the melancholy tween that I was in those days, I had more than enough taste for melodrama to tolerate the tortured YA fiction of Vedder's lyrics. And anyway, it wasn't really the stories in the songs that I connected with. What really moved me were the soaring choruses, the way Vedder's voice rides the cresting guitars. As with all anthems, the words relate more to themselves and to the music, than to any larger narrative, forming discrete, heavily charged instants of meaning. Over and over,

Ten reaches for, and often achieves, maximum emotional crescendo. "

Once upon a time I could control myself," "I'm still alive," "why go home?" "hold my hand, take a good look, this could be the day!"...you don't have to know or really care what these words are "about" to viscerally understand what they're communicating.

More than anything, though, it was Vedder himself that I related to. Up to that point my musical world consisted essentially of Guns 'n Roses, NWA, Public Enemy and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Some of these things are great, some are not, but none of these acts projected a personality that was anything like mine--which, of course, was a large part of the appeal. Theirs was a kind of hypertrophic manhood, a costume of rock-star machismo. Vedder, in contrast, radiated an unabashed, almost embarrassing sincerity. His ecstasies and pains and sorrows were transparent. His angst was almost campy,

but it was also unstintingly sincere. His early-'90's

emotionalism and the brooding anti-stardom that came later often scanned as pretension, but he came by them honestly and they were deeply felt. This

honesty, this emotional gravity, was nothing I had ever experienced in pop culture. The fact that these things, which were such powerful, ill-understood facets of my inner life, could actually be performed, could be physically expressed onstage or on record, totally blew me away.

Of course, sincerity and authenticity alone aren't enough to make great art, and they don't quite rescue

Ten from its excesses. (They, in fact, constitute those very excesses.) But those excesses, as well as the record's many strengths, make their fullest sense in the context of live performance, when the songs' anthemic qualities really shine. So I would turn your attention to Pearl Jam's live shows from that era. Because they are fucking amazing.

There are

a number of sources I could refer you to in order to back up this assertion. But for my money the best live documents of early Pearl Jam are

their first appearance on Saturday Night Live and

the band's set at the Dutch Pinkpop festival, both from the spring of 1992. In both performances, you'll see a band waking up to the startling realization that millions of people want to hear their music, that everything they'd ever imagined about their lives as musicians is coming true. They are freaking out.

You'll see a band of top-notch players totally inhabiting the music, really investing themselves in their songs, playing with ridiculous energy and heart. You'll see a singer bursting out of his own skin. He's spastically shaking his long, curly hair, grunting and wailing like he's in serious pain. He's gesticulating wildly, almost reenacting the stories of his songs. He's singing with a crazy desperation, as if communicating the message with insufficient urgency will literally kill him. He's flailing and shaking and falling over.

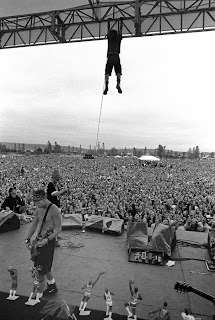

I know that this sounds painfully overwrought and theatrical. I totally hear you. Confessional self-expression is surely an overrated mode in pop culture. Rarely, though, are the emotions expressed so raw and so forceful. Even more important is Vedder's insatiable desire to communicate that emotion to an audience, to create a moment of shared ecstatic experience. Just look at him during "Porch", the band's triumphal set-closing jam. He climbs on a video crane, begs the operator to move it over the swarming crowd.

He leaps twenty feet from the crane into the sea of people. They swallow him up. There's a great generosity at work here, a commitment to sharing the cathartic thrill of performance, to dissolving the distinction between performer and audience. A handful of bands (Fugazi and Lightning Bolt come to mind) have achieved this kind of transfiguration in clubs and basements and parking lots. Vedder's gift--with the help of those anthemic, emotive songs--was to create that intimacy in front of thousands.

* * *

Then Pearl Jam did something strange. They recognized that their very sincerity and passion was being commodified, that the machinations of the culture industry were alienating them from both their audience and their music. And so--in a way that almost seems quaint now, given both the decentralization of the music industry and most current acts' un-ambivalent relationship with self-branding--they rebelled against that commodification. They stopped making videos; they stopped appearing on TV; they stopped granting interviews; they sued the country's largest ticket distributor. They abandoned the style that had made them famous and made

three increasingly hermetic, idiosyncratic, often bitter records.

And so while their music became more nuanced and textured (I think "better" might be another word for it), they were never quite as exuberant again, never quite as wide-eyed and manic. But I was hooked; the blood-curdling emotions, the intense pursuit of authenticity, these were things that were just too close to my heart to resist. I continued listening to Pearl Jam even as they came to look like alterna-rock dinosaurs next to the indie bands that comprised the majority of my tastes. I couldn't help myself. They were the inspiration for too many solitary bedroom rock-out sessions, too many epic concerts given to the mirror. When I was first figuring out who I was, they were the first band that actually felt like me.